#DEEP DIVE: What Caused Cardcaptor Sakura Fans To Be So Upset In 2003?

“#DEEP DIVE: What Caused Cardcaptor Sakura Fans To Be So Upset In 2003?”

If you’ve spent any time being a fan of anime, you’ve probably heard some rumblings about Cardcaptors, the localized American version of Cardcaptor Sakura. With localization and genre changes, it became a show fans of the original weren’t happy with and didn’t quite draw an audience like Kids WB hoped for. However, there’s more to the story. What caused such a drastic shift in excitement for Kids WB before the show first aired with regard to bringing the show to American audiences, to only being briefly mentioned by the network? How much of an investment was it to bring over the series? Why did the show not catch on over here like it did in Japan? And, most notably, why were fans still angry about the show’s localization nearly three years after it aired?

This tale, like most about anime at the beginning of the 21st century, begins with Pokémon. In 1999, Pokémon debuted on Kids WB and began to break record after record when it came to viewership and ratings. The series became a cultural touchstone in America, baffling people right and left, and entrenching itself into pop culture. Later in 1999, Nelvana Ltd., a Canadian animation company known for making children’s shows, acquired the rights to Cardcaptor Sakura from Kodansha. With how much success Pokémon had brought Kids WB, the network began to come up with an idea to bring a second anime series over with the hopes that it would also break out and become another hit. In the summer of 2000, Nelvana and Kids WB would come together to hopefully do just that when Cardcaptors debuted on June 17, 2000.

Prior to that June 2000 start date, Warner made sure people knew that Cardcaptors was coming to try and drive up hype around it. Their first unveiling of the series came in an April 2000 press release where not only could they brag about Pokémon ratings, but also that the company had their second Japanese series coming in the summer. The build on Cardcaptors’ debut continued when Warner unveiled their summer schedule, and several newspapers made mention of the series coming. With how much Warner had spent trying to build anticipation for what they thought would be their next anime hit in America, how did Cardcaptors fare in its debut?

At first, everything seemed to indicate that Warner had yet another hit on their hands. In its first month, ratings were solid in the general kids 2-11 demographic, with both boys and girls tuning in to see the show. There was even a piece in the Chicago Tribune dubbing Cardcaptors “the next big thing.” A good majority of people seemed to be predicting and expecting that there was going to be a new wave of anime merchandise hitting store shelves because of Cardcaptors, which was certainly evident by Nelvana getting 21 commitments for various forms of merchandise. Yet, despite the excitement after the first month, throughout the rest of the year, Warner started to talk less and less about Cardcaptors as the series fell down the press release mentions at the time.

In terms of business, one of the reasons Cardcaptors never truly blossomed into the “next big thing” was that, well, it wasn’t Pokémon. That’s a bit of an unfair critique to make since nothing airing at the time in terms of anime was doing the numbers Pokémon was consistently doing. It was the marquee show for a reason — in fact, nothing would come close for Warner until Yu-Gi-Oh!’s debut. But when you’re pushing the next Japanese series after you’ve already had a mega success, it would have been hard for Warner to feel that they had another success on their hands. When Cardcaptors’ second season launch came around, Warner again began promoting the show heavily, citing that it was in the top ten of broadcasts on Saturday morning and weekdays along with top five for girls on weekdays. While those are good statistics to flaunt, it wasn’t like when they could tell the media — and everyone else — that Pokémon was the number one show in multiple demographics. It also didn’t help that the growth of Cardcaptors hadn’t been nearly as substantial in its first year as Pokémon. The most they could muster up about Cardcaptors was that it was sixth behind multiple shows airing on the network.

Schedule shuffling didn’t help the series either. In 2001, the series would make its way to Toonami for a brief period, and later in the year would get pulled briefly from Kids WB, only to come back after a few weeks away. A series losing its spot in any context can be a scary thing as it immediately brings up questions about whether the series is getting canceled or not. Plus, it’s hard to maintain an audience when the series is shuffling in and out of the schedule. To be clear, Cardcaptors maintained a level of popularity well after its debut. If not, it would’ve been shelved by the network like what happened with Escaflowne. It also helped that Nelvana had a sizable financial interest in making sure the show was at least somewhat profitable and on television.

After the success of Pokémon, everyone wanted in on the anime pie. In order to do that, networks and production companies had to adhere to who they thought they could easily market anime to — American kids. That meant editing the source material to make it easier for that audience to understand and to air on television as Cardcaptor Sakura was originally a 70-episode series. While all of those episodes did not make it to air in America, Nelvana mentioned around the debut of the series that they were spending “roughly $100,000 on each episode to incorporate new music, scripts, and vocal tracks.” That seems like a lot of money, but with how much editing was happening to anime in this time period, it probably isn’t absurd, as other companies were potentially spending roughly the same. Al Khan, chairman and chief executive of 4Kids Entertainment at the time, told the Los Angeles Times in 2001 that “We spend a fortune on localization … We may spend another 50 percent of what we pay for them [in rights] just to localize [episodes].” To put that into perspective, if Nelvana maintained that same average per episode, they would’ve spent roughly $3,900,000 on the series with 39 episodes — a little over half of the actual series — that made it to air.

Even though Warner proclaimed that Cardcaptors was a top ten show for Kids WB, that didn’t mean fans were happy. A year after its debut, fans on message boards and around the internet were still upset with Nelvana’s changes to the series. That anger extended well past when the series was on television because around the final release of the non-broadcast version of Cardcaptor Sakura on home video in late 2003, fans were still upset as highlighted in an article in the Los Angeles Times. The lede of the article gets right to the heart of the matter: “Anime fans complain that WB has changed the characters and plots of the ‘Cardcaptors’ series to broaden its appeal in the U.S.” All things that were true.

As mentioned earlier, localization changes for anime during this time period were the norm. Large-scale edits had been an issue even before the boom with series such as Robotech/Macross, and of course, Sailor Moon, another magical girl series that was a prime example of a show that was heavily localized. Nobody would have allowed unedited/unlocalized anime to air on their children’s programming blocks. For fans who wanted to view the source material in its original form, other routes had to be pursued. The problem that occurred with Cardcaptors is with how much localization they did to the show.

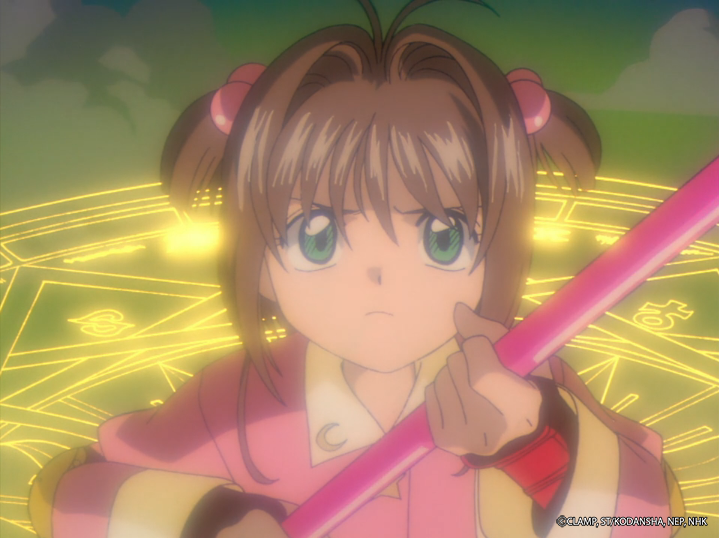

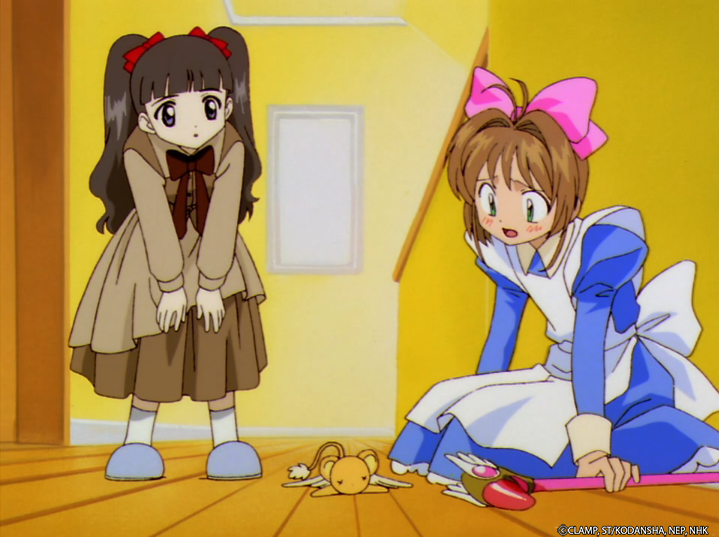

Other shows could get away with occasional localization changes to make it more understandable for American audiences. A name change here, a different joke there, and it’s easy to help adapt a show to suit new viewers without completely revamping everything. Cardcaptors went above and beyond by changing names, plot points, the episode order, removing any instances of homosexuality in the plot, and attempting to completely change the genre from magical girl to action and making boys the main target of marketing rather than girls. This issue was so bad the series had two different home video releases — one of the broadcast version and another that was an attempt to bring over the original version of Cardcaptor Sakura to appease fans. It certainly makes the $100,000 figure make sense but is also a lot of work to completely overhaul a show for young girls to a series for young boys.

At the time, John Hardman of Kids WB insisted that the changes to the series were minor, but confirmed that they explicitly marketed the show to young boys, saying, “We asked them to take the female hero’s name out of the title and turn it into a more gender-neutral title that wouldn’t turn away our core boy audience.” Along with that, there were marketing images that showed Syaoran front in center with Sakura behind him. From a business standpoint, that makes sense. The demographic that was coming out to watch other Kids WB shows at the time was boys. Kids WB, Fox Kids, and Cartoon Network were all vying for boys to watch their shows. They weren’t going to change that philosophy to appeal to girls because they weren’t coming out in droves to make their shows incredibly popular. To the networks, girls were just an added bonus to help drive numbers up, and that’s it.

Cardcaptors certainly became the show that personified fan passion and outrage — it also was one of the first shows of the anime boom period in America to pose the question of how we should localize anime. It’s a show that’s become infamous for the wrong reasons and is almost a folk tale at this point as more modern fans that want to see the show can watch the original version, while the original Cardcaptors broadcast is slowly becoming lost to time. Cardcaptors was never going to become as big as Pokémon, but it’s possible it could’ve done well if it had stuck to its magical girl roots. It might not have drawn as much of the boys demographic by doing so, but maybe it could have brought more girls to watch anime and created a world where more anime targeted to girls got a chance in America. The reality we live in, though, is that Cardcaptors was an attempt to make the next big anime series after Pokémon, but ultimately, it wasn’t.

You can watch Cardcaptor Sakura in its original form as it was intended right here!

Jared Clemons is a writer and podcaster for Seasonal Anime Checkup and author of One Shining Moment: A Critical Analysis of Love Live! Sunshine!!. He can be found on Twitter @ragbag.

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features!

If you liked the article, do not forget to share it with your friends. Follow us on Google News too, click on the star and choose us from your favorites.

For forums sites go to Forum.BuradaBiliyorum.Com

If you want to read more anime-manga articles, you can visit our anime-manga category.