#IN-DEPTH: Unraveling the Ecology Behind My Favorite Anime and Manga

Table of Contents

“#IN-DEPTH: Unraveling the Ecology Behind My Favorite Anime and Manga”

Ecology is a widely misunderstood term that is often confused with environmentalism. The word "ecology" originates from the Greek word oikos (home or household). As that suggests, ecology is the study of the organism and its oikos — its home or environment. Land, water, air, sunlight, plants, animals, other individuals of the same species, and itself — everything is part of an organism's environment along with the way everything relates to everything else. That’s ecology.

Most information on ecology is in the form of research papers, textbooks, and popular science. In short, nonfiction. We may read nonfiction books on topics we are interested in, but for topics we aren’t interested in or even aware of? It’s unlikely. Fiction bridges the gap between education and enjoyment. You may not want to watch a documentary about agriculture, but you’d certainly be interested in watching Silver Spoon. It’s a win-win.

Anime and manga have always had an interesting way of approaching topics of nature and ecology, whether it be a celebration of nature like A Place Further Than the Universe, a subtle treatise on ecological topics like Parasyte, or environmental commentary like Weathering With You. Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind is probably the most important anime/manga piece of eco-fiction. These are all important works, but let's look at the ecological themes in three of my most treasured anime and manga, each of which embodies a different branch of ecology.

Shin Sekai Yori (From the New World) and Behavioral Ecology

From the New World might have the most overt connection to ecology. Author Yusuke Kishi was inspired to write the original novel after reading Konrad Lorenz’s 1963 book On Aggression. Konrad Lorenz is widely considered to be the father of modern behavioral ecology, perhaps best known for his studies on imprinting in geese. In On Aggression, Lorenz attempted to explain aggression (defined as the intent to harm another individual of the same species) through the framework of evolutionary biology. According to his (now outdated) "hydraulic model," frustration builds in the individual like a fluid until it is "released" by an outlet — namely, aggression.

Aggression is a curious phenomenon. You are probably accustomed to seeing animals in grand fights to the death in nature documentaries. Except, this actually almost never happens. All organisms seek to be as "successful" as possible. In evolutionary terms, "success" comes from leaving behind as many descendants as possible. Can’t do that if you’re dead, can you? Even injuries have the potential to impact success: an injured individual might be viewed as an undesirable mate, for example. Animals will actively avoid violent escalation of conflict as much as possible — especially social animals where conflict is an inevitable byproduct of increased interaction, and powerful carnivorous animals who have the capability to kill. Lorenz wrote of how these animals must evolve behaviors that will reduce the impact of aggression. One of these anti-aggression adaptations might sound familiar to From the New World fans: attack inhibition.

In From the New World, attack inhibition is one of the key properties of humans with the psychokinetic powers called Cantus. Basically, a human with Cantus will feel strongly unable to physically attack another human. Persisting with such an attack will result in the triggering of "death feedback," killing the attacker. This is similar to natural phenomena — fights among wolves or dogs usually have a clear winner and loser but rarely end in serious injury because bite strength is carefully moderated so as not to cause injury (a phenomenon called soft mouth). The loser will turn upside down, exposing their vulnerable regions to the winner, who will not attack as they have already established dominance. Similar behaviors can be observed in many other animals, such as ravens. According to Lorenz, this is the result of an innate attack inhibition that has evolved in these species.

While the “death feedback” of From the New World might seem like a harsh punishment for aggression, it’s not too far off from the truth. A species whose individuals engage in wanton violence is not a species that would last long. In the words of Lorenz, “a raven can peck out the eye of another with one thrust of its beak, a wolf can rip the jugular vein of another with a single bite. There would be no more ravens and no more wolves if reliable inhibitions did not prevent such actions.” In other words, violent escalation of conflict is undesirable for the individual, and by extension for the species. Natural selection is real-life “death feedback,” isn’t it?

Lorenz also had a theory that less-powerful animals such as doves or rabbits have not evolved such inhibitions because they aren’t as necessary — except in captivity, where individuals are forced to confront each other with no possibility of escape. And what of us normal, Cantus-less humans, then? Lorenz describes us as "a dove which, by some unnatural trick of nature, has suddenly acquired the beak of a raven." In From the New World, the supposed “greatest danger to society” comes in the form of humans with weak or nonexistent Cantus — these individuals are not burdened with attack inhibition or death feedback. In short, individuals like you or me. Humans are a curious species, even without Cantus. Our use of tools bypasses conventional evolutionary pathways. We have not had time to adapt, but will we? Are war and conflict an inevitable byproduct of our aggressive tendencies? Both Lorenz and From the New World have one common thing to say: that there are no easy answers to this.

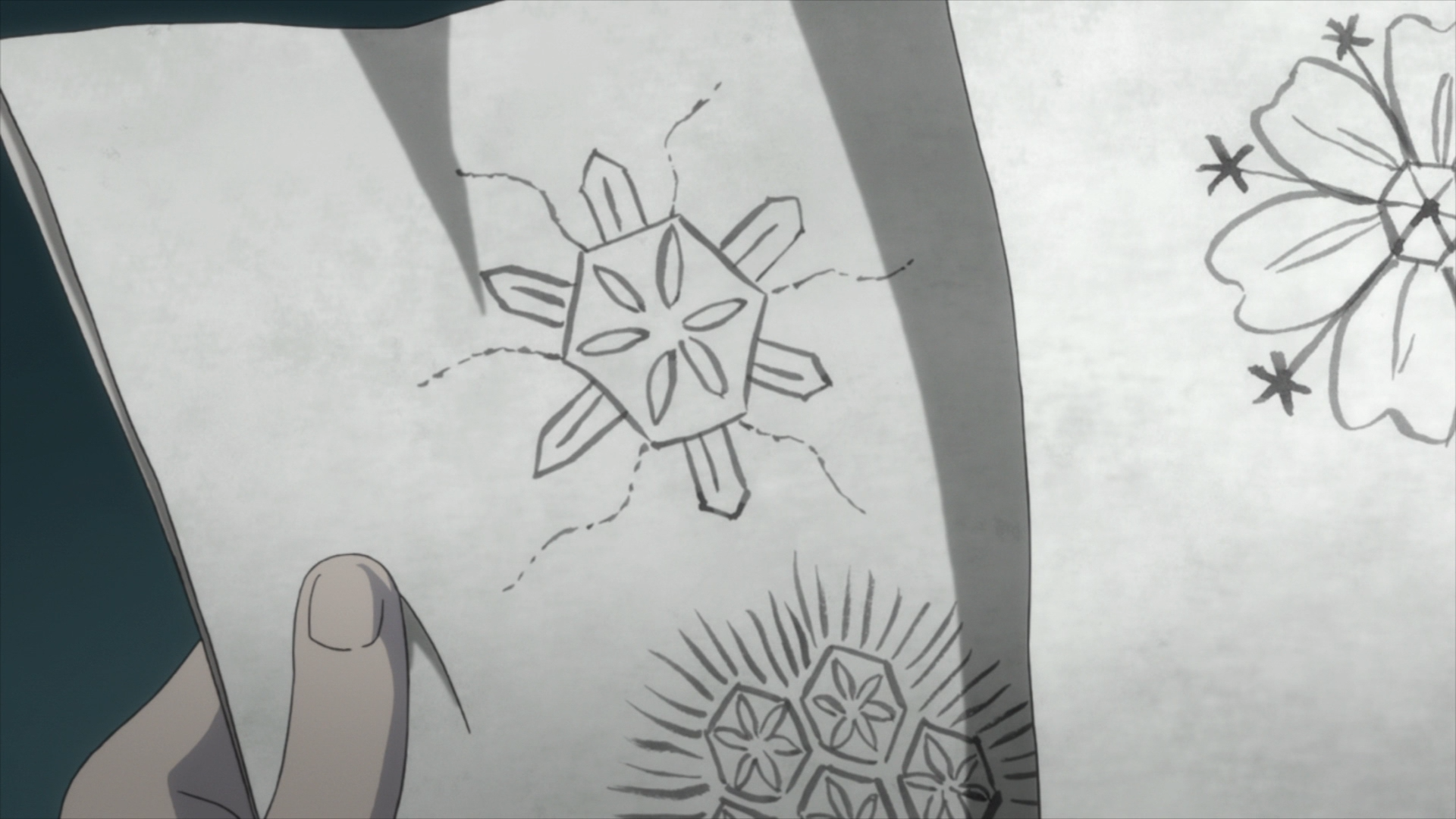

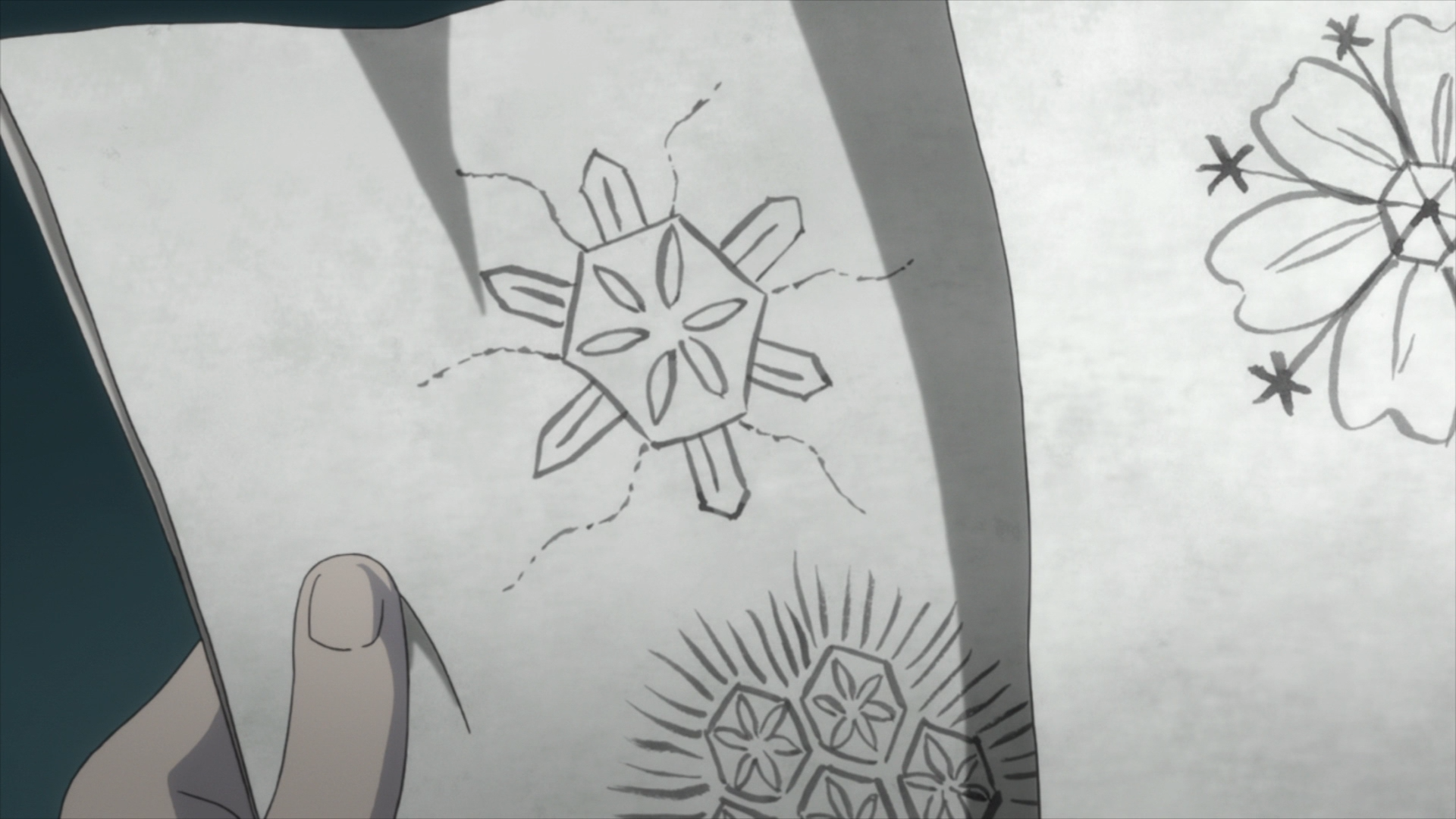

Golden Kamuy and Conservation Ecology

Golden Kamuy is an ecologist’s paradise. Manga creator Satoru Noda packs pages with everything from delicate drawings of local flora to elaborate footnotes on the pooping habits of bears, really bringing early 20th-century Hokkaido to life. On the surface, Golden Kamuy is a classic gold rush western, a wild tale of conflict between the protagonists (ex-soldier Sugimoto and Ainu hunter Asirpa) and various other parties in search of lost Ainu gold. Beneath lies a greater conflict: humanity versus Hokkaido itself.

Hokkaido is Japan’s largest prefecture, and one of its least-populated, accounting for 22 percent of Japan’s land area but only 4.4 percent of the population. Hokkaido is an island, physically separated from mainland Japan to the south by the Tsugaru Strait. This physical separation is known as Blakiston’s Line (after English explorer Thomas Blakiston). Several plants and animals found north of Blakiston’s Line (in Hokkaido) won’t be found south of it (in mainland Japan), and vice versa. So you have black bears and flying squirrels on the mainland but brown bears and chipmunks in Hokkaido.

Into this unique environment stepped modern human civilization in the form of settlers from mainland Japan and beyond — mostly ranchers, gold prospectors, and prisoners. In short, the majority of the Golden Kamuy cast. Although the Ainu people had lived in Hokkaido for a long period of time, their impact on the environment was minimal, as they lived sustainably off the land. The settlers were a different bunch, altering the environment in many ways. One of those ways was through farming. The Meiji government sought to modernize agricultural techniques in the country and brought in advisers from the West to do so. One of them, in particular, would change the landscape of Hokkaido for good — a certain Ohio rancher named Edwin Dun, who you might recognize as Eddie Dun from Golden Kamuy.

Well before his first appearance in Volume 7, Dun’s role in de-wilding Hokkaido was hinted at in Volume 3 — Noda mentions an American rancher responsible for driving the Hokkaido wolf to extinction. Brought in to introduce scientific agricultural methods in 1873, Dun realized horse ranching in Hokkaido faced a significant hurdle: predation. Hokkaido wolves were slaughtering a good portion of horses and foals, so Dun took it upon himself to exterminate wolves from Hokkaido. His method of poisoning horse carcasses, combined with a bounty hunting system, worked a little too well — the last record of the Hokkaido wolf is from 1896.

The other major way settlers impacted the environment of Hokkaido was through the very foundation of Golden Kamuy’s plot: gold mining. It has been well documented that even small-scale gold panning at rivers has serious consequences for fish populations — the mining activity disturbs the riverbed and increases the amount of sediment in downstream waters. This sediment contains greater levels of mercury and other trace minerals that can impact fish. The Hokkaido gold rush endangered the salmon of Hokkaido — one of the most important species of the ecosystem as a food source to bears and Ainu alike.

Ultimately, Golden Kamuy is as much a study of human-nature conflict as it is of conflict between humans. Each of the three main factions of people — settlers, soldiers, and Ainu — view nature differently. To settlers like Eddie Dun, nature is an inconvenient hurdle to be tamed. To soldiers like Lieutenant Tsurumi, nature is a powerful hazard to their daily lives that is to be feared. And to Ainu like Asirpa, nature is an equal, meant to be treated with respect.

MUSHI-SHI and Community Ecology

MUSHI-SHI's central concept of enigmatic life-forms — called mushi — that flit on the edge of existence, enables it to tackle a whole bunch of ecological themes, but central to it all is what is known as community ecology. Community ecology studies the way different organisms interact at various scales in space and time. At the core of this field are interspecific interactions — how different species interact with each other. An interaction between two species could be anywhere between mutualism (where both parties benefit) or parasitism (where one exploits the other).

The depiction of parasitism is extremely close to real life. Some mushi take over the host’s ears, some take over the eyes. Some take control of the entire body, leaving but a husk of a person behind. This horrifies us because, as humans, we aren’t really accustomed to parasites aside from the occasional hair lice or intestinal worms. To see the worst of parasitism, one needs to look at other species. Parasitoid wasps will "drug" large insects by stinging them before laying eggs inside them, when the young hatch, they can eat the host alive from the inside out. Why not outright kill the host? To keep them fresher for longer.

The most intriguing parasites are those that alter the host’s behavior to their benefit. In Episode 3 of MUSHI-SHI The Next Passage, we encounter a man who seems to shun warmth of any kind, embracing the cold of winter. The most notable thing is the fact that he is not truly cold-resistant — his body is suffering from the effects of exposure, yet he seems not to notice. Unbeknownst to him, he is infected by a cold-loving mushi. This is textbook behavior alteration. Behavior-altering parasites have some of the most complex life-cycles of any organism. Toxoplasma, a small microorganism, infects rats. However, its true host (the one in which it can reproduce) is the domestic cat. To ensure that it reaches a cat, the Toxoplasma alters the behavior of its rat host, making it braver and less fearful of cats. Once this foolhardy rat is eaten by a cat, the Toxoplasma can finally reproduce, releasing spores via the cat’s droppings, ready to be eaten by — you guessed it — a rat. Thus the cycle starts over. This isn’t an isolated case — there are hundreds of such parasites, some with even more complex life cycles.

No episode of MUSHI-SHI better encapsulates the ecology of parasitism than the Rosemary’s Baby-esque “Cotton Changeling” (Season 1, Episode 21). We encounter a mother and her strange, green-skinned, near-identical children. These "children" are not human — they are merely mushi pretending to be human. While the first "children" are barely able to walk, later generations are impressively human-like, with fully developed speech and intelligence. They resist protagonist Ginko's attempts to convince the mother to stop caring for them. This generational improvement mirrors nature, where parasites are engaged in an evolutionary arms race with their hosts. The hosts change to counter the parasite, and the parasite must keep pace too. A classic example can be seen with that most classic of parasites: the cuckoo. Over time, host birds learn to recognize cuckoo eggs or chicks and throw them out. In response, the cuckoo begins to lay eggs that are more similar to those of their host.

If you thought parasitism was solely about harming the host, you’d be wrong — MUSHI-SHI understands this. In many episodes, mushi infection actually confers a benefit upon the infected person, who are sometimes unwilling to be cured by Ginko. Once again, this isn’t far off from real life. Researchers now believe there is a spectrum between mutualism and parasitism. In fact, many mutualisms began as parasitic interactions. One of the most widespread parasites — bacteria called Wolbachia that infect insects — confers benefits like viral immunity and insecticide resistance upon its host. Some insects are incapable of breeding without Wolbachia infection. But if you thought the Wolbachia was doing this out of benevolence, you’d be wrong again — Wolbachia is simply committed to doing whatever it takes to ensure its own survival. If the host dies, so does the parasite.

Host-parasite interactions are cyclic, and MUSHI-SHI is all about such cycles. Shots of humans and mushi are contrasted with long shots of the forest floor, where leaves decay and rot, returning to soil, fueling the web of life. Mushi exploit humans, who exploit mushi, and the cycle continues. At the center of it all is Ginko, an ecologist if I’ve ever seen one. To Ginko, the mushi are neither good nor evil, they simply exist. Everything is only the way it should be, nothing more or less. Taking on the role of a neutral observer rather than an exterminator, he goes from place to place, motivated as much by his own curiosity as he is by a desire to help people. It is through Ginko that MUSHI-SHI shows us what it means to be an ecologist.

The Power of Fiction: A Personal Story

I mentioned earlier that fiction has the power to make us interested in things we aren’t interested in. It also has the power to make us regain interest in things we lost interest in. I was once an ecologist-in-training. Since childhood, I had been fascinated by the natural world, and becoming an ecologist seemed like the natural culmination of such interests.

It didn't pan out that way, sadly. I hated college. By the end of my long and protracted Master’s degree, I no longer had any love for ecology. I actively shied away from scientific discussions with my more illustrious colleagues and no longer made an effort to keep myself informed about current research. Me and ecology, we were finished. Or so I thought. I began to explore anime and manga — longtime interests of mine — more deeply as a sort of escape from my "failures" in academia. It was through the three titles discussed above that I was able to reconcile with the subject. My ecological knowledge actively enhanced my watching and reading experience and I suddenly felt a desire to rediscover what it was that made me love the subject so much in my early days. I was genuinely grateful for everything I'd learned because it helped me better appreciate such fine works of art. While I may never return to academia, I no longer feel the need to forget my time there, to push it out of my memory. I no longer feel that shame. It goes to show that anime and manga not only have the power to teach us about our world but can also touch our lives in strange and unexpected ways.

If you liked the article, do not forget to share it with your friends. Follow us on Google News too, click on the star and choose us from your favorites.

For forums sites go to Forum.BuradaBiliyorum.Com

If you want to read more anime-manga articles, you can visit our anime-manga category.