#Is Einstein’s theory of gravity still relevant — we put it to its toughest test yet

Table of Contents

“#Is Einstein’s theory of gravity still relevant — we put it to its toughest test yet”

General relativity is not only very accurate but ask any astrophysicist about the theory and they’ll probably also describe it as “beautiful”. But it has a dark side too: a fundamental conflict with our other great physical theory, quantum mechanics.

General relativity works extremely well at large scales in the Universe, but quantum mechanics rules the microscopic realm of atoms and fundamental particles. To resolve this conflict, we need to see general relativity pushed to its limits: extremely intense gravitational forces at work on small scales.

We studied a pair of stars called the Double Pulsar which provide just such a situation. After 16 years of observations, we have found no cracks in Einstein’s theory.

Pulsars: nature’s gravity labs

In 2003, astronomers at CSIRO’s Parkes radio telescope, Murriyang, in New South Wales discovered a double pulsar system 2,400 light years away that offers a perfect opportunity to study general relativity under extreme conditions.

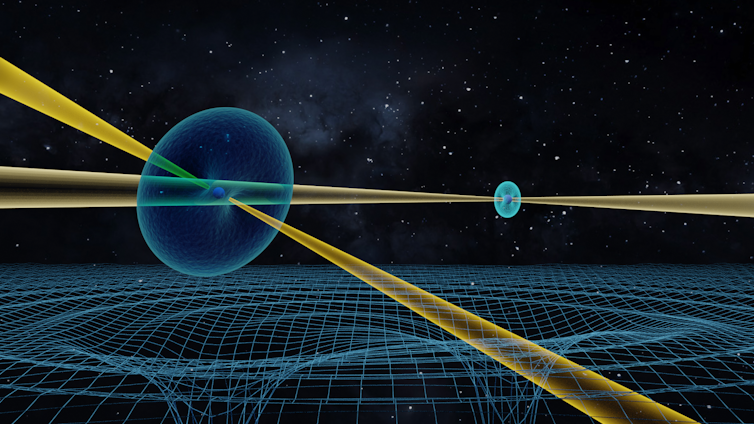

To understand what makes this system so special, imagine a star 500,000 times as heavy as Earth, yet only 20 kilometers across. This ultra-dense “neutron star” spins 50 times a second, blasting out an intense beam of radio waves that our telescopes register as a faint blip every time it sweeps over Earth. There are more than 3,000 such “pulsars” in the Milky Way, but this one is unique because it whirls in an orbit around a similarly extreme companion star every 2.5 hours.

According to general relativity, the colossal accelerations in the Double Pulsar system strain the fabric of space-time, sending gravitational ripples away at the speed of light that slowly sap the system of orbital energy.

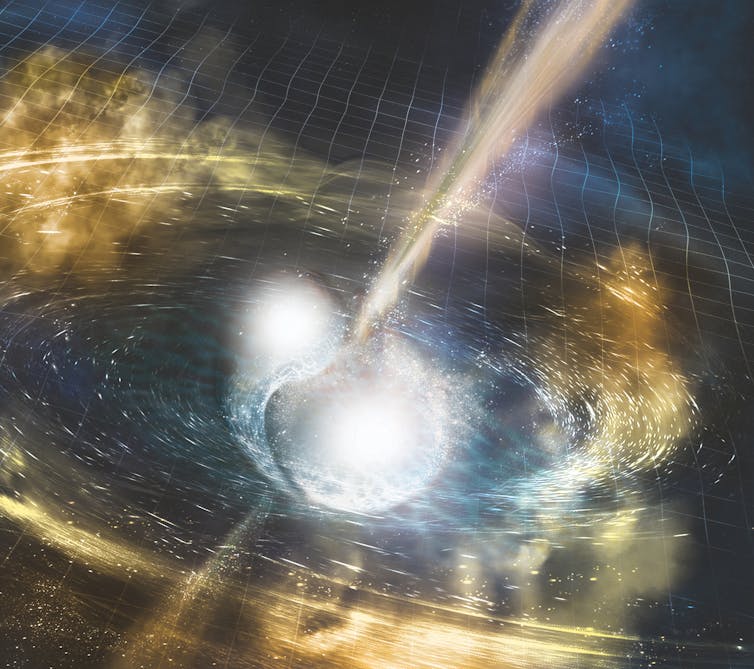

This slow loss of energy makes the stars’ orbit drift ever closer together. In 85 million years time, they are doomed to merge in a spectacular cosmic pile-up that will enrich the surroundings with a heady dose of precious metals.

We can watch this loss of energy by very carefully studying the blinking of the pulsars. Each star acts as a giant clock, precisely stabilized by its immense mass, “ticking” with every rotation as its radio beam sweeps past.

Using stars as clocks

Working with an international team of astronomers led by Michael Kramer of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany, we have used this “pulsar timing” technique to study the Double Pulsar ever since its discovery.

Adding in data from five other radio telescopes across the world, we modeled the precise arrival times of more than 20 billion of these clock ticks over a 16-year period.

To complete our model, we needed to know exactly how far the Double Pulsar is from Earth. To find this out, we turned to a global network of ten radio telescopes called the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA).

The VLBA has such high resolution it could spot a human hair 10km away! Using it, we were able to observe a tiny wobble in the apparent position of the Double Pulsar every year, which results from Earth’s motion around the Sun.

And because the size of the wobble depends on the distance to the source, we could show that the system is 2,400 light-years from the Earth. This provided the last puzzle piece we needed to put Einstein to the test.

Finding Einstein’s fingerprints in our data

Combining these painstaking measurements allows us to precisely track the orbits of each pulsar. Our benchmark was Isaac Newton’s simpler model of gravity, which predated Einstein by several centuries: every deviation offered another test.

These “post-Newtonian” effects – things that are insignificant when considering an apple falling from a tree, but noticeable in more extreme conditions – can be compared against the predictions of general relativity and other theories of gravity.

One of these effects is the loss of energy due to gravitational waves described above. Another is the “Lense-Thirring effect” or “relativistic frame-dragging”, in which the spinning pulsars drag space-time itself around with them as they move.

In total, we detected seven post-Newtonian effects, including some never seen before. Together, they give by far the best test so far of general relativity in strong gravitational fields.

After 16 long years, our observations proved to be amazingly consistent with Einstein’s general relativity, matching Einstein’s predictions to within 99.99%. None of the dozens of other gravitational theories proposed since 1915 can describe the motion of the Double Pulsar better!

With larger and more sensitive radio telescopes, and new analysis techniques, we could keep using the Double Pulsar to study gravity for another 85 million years. Eventually, however, the two stars will spiral together and merge.

This cataclysmic ending will itself offer one last opportunity, as the system throws off a burst of high-frequency gravitational waves. Such bursts from merging neutron stars in other galaxies have already been detected by the LIGO and Virgo gravitational-wave observatories, and those measurements provide a complimentary test of general relativity under even more extreme conditions.

Armed with all these approaches, we are hopeful of eventually identifying a weakness in general relativity that can lead to an even better gravitational theory. But for now, Einstein still reigns supreme.![]()

Article by Adam Deller, Associate Investigator, ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Waves (OzGrav), and Associate Professor in Astrophysics, Swinburne University of Technology and Richard Manchester, CSIRO Fellow, CSIRO Space and Astronomy, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If you liked the article, do not forget to share it with your friends. Follow us on Google News too, click on the star and choose us from your favorites.

For forums sites go to Forum.BuradaBiliyorum.Com

If you want to read more like this article, you can visit our Technology category.