#Cast, Director Go Behind Broadway Revival – The Hollywood Reporter

Table of Contents

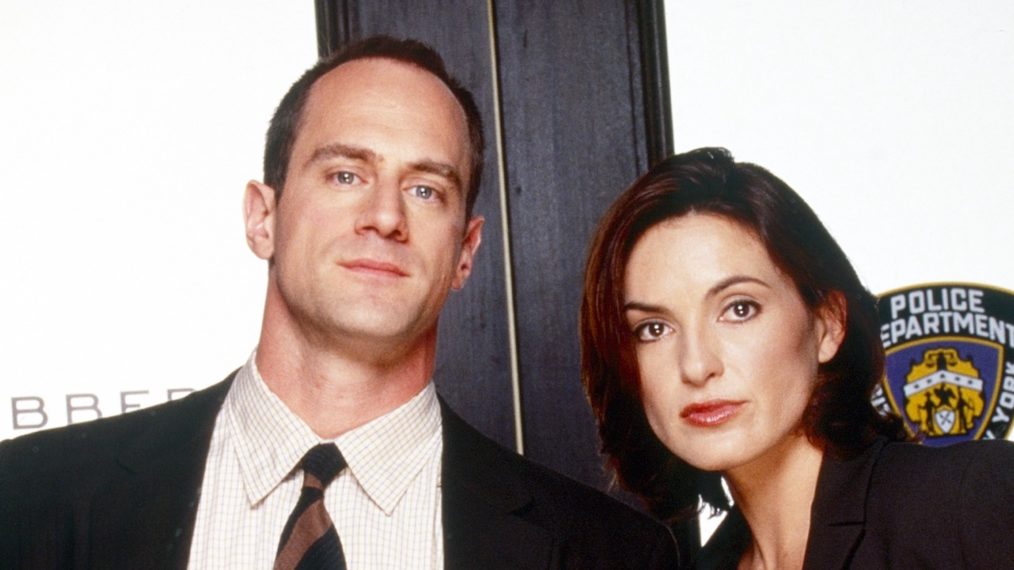

Cast, Director Go Behind Broadway Revival – The Hollywood Reporter

“August Wilson had this amazing innate ability to capture our history, our story, our cultures, our dreams, our hopes, our fears, our wants and desires — all of it within the American Century cycle,” The Piano Lesson producer Brian Anthony Moreland tells The Hollywood Reporter over the phone in December. “But what sets The Piano Lesson apart [in the Century Cycle] is easy. It’s legacy. It has always been about legacy.”

Since opening in October, The Piano Lesson has offered theatergoers a chance to reexamine both the legacy and lessons of all of Wilson’s work through its single story — now the late writer’s highest-grossing play and highest-grossing revival of any play on Broadway. It’s an opportunity that has brought to the fore the unique relationship the playwright’s work frequently has not only with audiences, but the Black artists across generations who serve as the beneficiaries and guardians of a seemingly timeless body of period work.

Moreland proudly counts himself among that community of Black creatives selected to impart Wilson’s version of the history and, in some ways, the present of Black Americans. It’s a journey he says started with an invite by the Wilson estate and a weekend in Pittsburgh with the playwright’s widow Constanza Romero Wilson. “What she was really wanting and needed to happen and [felt was] missing was the August Wilson for now, that would move people toward the words and the work and it to this new generation of people,” he recalls.

Moreland would soon after find himself in conversation with actor-producer Denzel Washington, who has taken to shepherding the late writer’s work on the screen, and later LaTanya Richardson Jackson, the revival’s director. Across the table at breakfast, the first woman to helm a Wilson production on Broadway asked Moreland a simple, but important question. “So are you team Berniece or Team Boy Willie?” Moreland returned to the concept of legacy with an answer that was quick and sure: “I said I’m team Berniece.”

For Richardson Jackson, stepping into the role of director meant making intentional adjustments to the show in a way that would elevate the perspective of Berniece Charles (Danielle Brooks), a Black widow and mother who spends the play trying to stop her brother, Boy Willie (John David Washington), from selling a 130-year-old piano with the faces of their enslaved ancestors carved into its wood. He wants to sell that heirloom for a plot of land those ancestors once toiled on, a purchase he’d make from the brother of Sutter, the white man whose family once owned enslaved members of the Charles family — and who killed their father.

It’s an approach that doesn’t change a single word of Wilson’s, but that ultimately allows the director and her ensemble of Broadway debuts and veterans to better get at what’s underneath the story’s main conflict about a brother and sister who embody an eternal conflict of Black Americans. That is, whether to preserve a past some want to be forgotten or attain a future untethered to what one was once denied.

“The conflict is between Berniece and Boy Willie in the setup, but the duality of their relationship is a constant in that play like it is between Doaker and Wining Boy; between Lymon and Boy Willie; Lymon, Boy Willie and Avery; between Berniece and everybody. All of these are just a series of relationships and how they interact with each other towards the climax, the denouement” she explains. “So what does everybody want, including Sutter?”

It’s a basic but signifigant question that not only fuels the characters’ stances on whether to keep or sell the instrument, but the show’s exploration of the spirituality and racism generationally tied to it and them family. It also gets directly at an even larger concept underscoring the entire Pittsburgh Cycle: How are Black Americans’ present and futures shaped — or even haunted — by both the forces of their individual and collective pasts?

THR spoke with several of the play’s stars, including Samuel L. Jackson, Washington and Brooks, along with Moreland and Richardson Jackson, about how their critically acclaimed revival brings new meaning to their careers and the fourth chapter in Wilson’s 10-play series.

Richardson Jackson’s Turn at the Helm Is Focused on Making Wilson in a Modern Way

In her Broadway directorial debut, Richardson Jackson says she wanted to honor the playwright’s original intentions while delivering the story through a lens it hadn’t quite been told before. That resulted in certain themes and arcs of the play that might resonate more with modern audiences feeling pronounced.

LATANYA RICHARDSON JACKSON Lloyd Richards did the original and he did such a job. It was perfection, so you can’t go back to that. And why would you want to try to go back to that? Revivals should be reimagined and we shouldn’t try to regurgitate what was already done.

SAMUEL L. JACKSON What connects the most [in this production] — it’s the fact of generational wealth. You’re immediately passed the ghost story, pressed into being team Berniece or team Boy Willie and the validity of both of these arguments. When I was doing the play, we weren’t even discussing generational wealth. It was not even a term 30 years ago. So this is a story that’s easily relatable because everybody has something. Somebody will die and they leave something and the family will start fighting over it — either it’s a house or some dishes, a car or some money. Always some money. People understand not wanting one relative to get some or wanting to keep these very specific things in the family.

BRIAN ANTHONY MORELAND With The Piano Lesson there’s the argument of you got this thing sitting in the house taking up space and you’re not playing it, you’re not teaching lessons on it — nothing. It’s sitting there collecting dust, so why not give it to me so that I can sell it? I understand that argument. But then you don’t understand what that thing did to me or what it did to us or what it has done for us.

RICHARDSON JACKSON I decided my first obligation was to the intention of August’s work and only the second was my vision, and my vision was to place the mirror in front of the entire family. For them to see the similarities and to see the differences of how they were navigating our life and our cultural situation in this country — the conflicts that they had to grapple with in the instance they were confronted. I answered a lot of what I felt were the questions regarding who they were to each other. What was their initial conflict in the play? What were they there to do? It was different with each one.

JACKSON It’s a whole different attitude about who they are in the way that [LaTanya] directed the play. She wanted to make sure that there was a family dynamic there that had love at the core of it. We didn’t necessarily have that when I [first] did it. Boy Willie was almost like the adversary and Berniece was a victim of bullying.

JOHN DAVID WASHINGTON Her keen sense of family and understanding very much so about what it is growing up in the South was paramount. It was crucial to unlocking the freedom to have when you’re expressing yourself on that stage. It introduced to me possibilities. There’s more of a variety of emotions that come out. There’s more of a discovery that comes out if you’re layering it and letting the tension build — not the anger, but the frustration. That works because you care so much. Because you love so hard. I can get angry at a stranger but I get frustrated with someone that should know better, somebody that I trust. It becomes either disappointment or letdown — and that’s more dangerous.

Richardson Jackson’s Experience as a Black Woman Added Depth to Berniece’s Position and Portrayal

Those involved with the production say elements of the production process presented different — and, in certain instances, deeper — experiences than the show’s cast and crew might have had with a male or white helmer. That proved to be particularly beneficial when telling the story of Berniece and the real Black women who serve as the protectors and arbiters of their family’s history.

RICHARDSON JACKSON When Sam did Piano Lesson at Yale, I got to meet August and talk to him. I was acting then a lot, so for me, I was looking for the women who were in his plays as deep as these men were. I said, “You’ve got to give a play that’s just all about the women.” He said, “Well, when I know what women think, the way I know how men think, I’ll do that.” I never forgot that. (Laughs) I said, “OK, I’ll roll with that because you know what you’re writing.” It’s just that I want so much more of it. The different women in his plays, the way that we are portrayed is so insightful, true and pure.

MORELAND The discussion that we had about Berniece was really about the fact that August has never written specifically for women and with LaTanya being a woman, she had those same innate characteristics, traits and responsibilities as a bearer of knowledge of the past, the present and the future as Berniece — in terms of knowing what it is to hold on to tradition and hold a family together. These are all things that were within LaTanya as a singular woman, so we had that at the helm as our source and could filter that source through the lens of Berniece giving life, giving birth, holding culture, holding past, holding present, giving future as a singular woman.

BROOKS [Berniece’s] dealing with so much alone: being the matriarch of the family, being a widow at 32 years old, being a mother — just the responsibility that she carries is pretty weighty. She is a Black woman who has been taught the way in which women are supposed to be in the world — her values, her ideas — but I think post-Crawley’s [Berniece’s husband] death, she is really elevated and is beyond her time. When I talk about [Avery] trying to tell me a woman can’t be nothing without a man — when I go into this monologue with all these questions about how am I supposed to raise this child by myself and just the weight of what a lot of Black women are experiencing day-to-day — it is something that was very relevant in the ’30s and I think is still relevant to today.

RICHARDSON JACKSON To have someone as young as Danielle playing Berniece became one of our challenges because how do you explain a woman in 1936 and what she was allowed to do and then give her a feminist speech like she has in the scene with Avery when she stands up to him? That’s a very feminst turn to me and is very modern. How does a young person playing her deal with the characterization of this woman when all she wanted to do really was say, “Oh, no, I’m gonna speak to him this way.” We tried to find things that were natural to the experience of women then — like she makes the bed. It was 1936 and there were certain cultural manifestations of being a woman that just were. But then with that monologue, here was her moment.

DANIELLE BROOKS I think it’s been pretty incredible to be led by this Black woman. I admire her and what she’s brought to the evolution of what we can do as Black artists. Being the first woman to direct an August Wilson on Broadway — that’s huge. Artistically, it was heaven because I didn’t have to explain myself a lot of the time. When we talked about doing Maretha’s hair and having that press and comb, we didn’t have to have a conversation about that. I already knew what it smelled like and I already knew what that felt like, the weight of it in my hand and the heat. And because Ms. LT is more familiar with that time period and a woman from the South like myself, she was able to school me a bit more. She was able to bring more perspective to it.

RICHARDSON JACKSON I determined that I wasn’t going to be a man in this. Sometimes we do ourselves a disservice because we’ll say, “Oh, that woman got in that position and she immediately turned into a man or tried to do it like a man.” I said I don’t believe in that bullshit. I just went into it knowing that God’s got my back and tried to help them open themselves up to what the moment is of what August is saying.

The Shift to Better Understanding Berniece’s Perspective Isn’t Interested in Sacrificing Wilson’s Exploration of Black Malehood

Despite understanding Berniece’s desires, Richardson Jackson wasn’t interested in watering down the show’s men, including Boy Willie, into monolithic representations. Wilson’s male characters each embody “a different kind of Black man, which allows the complexity of differences inside the community.” It’s a collection of shared experiences and intimate personal differences that speak clearly to Wilson’s historical retelling of the Black American experience.

RICHARDSON JACKSON I was determined to reimagine the play for a new generation without, contrary to what some people might think, endangering the intention of what August was doing with these men — what the words were doing and what his intentions were.

MORELAND I honestly don’t know of many other playwrights that write in a way that gives Black men this much space, time and presence to share.

JACKSON When I was a kid, not having a father, I had my grandfather and his brothers. They were old guys that I sat around and played cards with when I was like six and seven years old, or just listening to him talk while he sat around, drank and smoked. Those are the guys that August writes and if you met those guys, this is a total homage to who they are.

WASHINGTON When we talk about Black masculinity, there’s that moment they’re singing, “Berta, Berta.” We all come from different places, different generations, but the commonality is what? Jim Crow South. It’s the system. It’s Parchman farm, which is one of the worst prisons in America. It’s still active today. So if they did come back, they share that and how we’ve been able to survive all these different things. And they turned it into a song. I think even the way they use the N-word, how they have been able to turn this into terms of endearment or they use it as armor, as how to get over something.

And Boy Willie hasn’t really talked about losing his father until these moments in the play. They really haven’t had any closure about Crawley until the moments of this play. It’s been three years since he’s seen anybody, so he’s so excited just to be around them. Probably what kept him alive in prison is knowing the love that was waiting on him in Pittsburgh. So these moments of contention that are seen in the play, or this masculinity that is expressed, it’s all on the bedrock of love. And that love gives [Boy Willie] the security and the ingenuity — the confidence — to know that he’s right about what he’s talking about.

JACKSON Boy Willie has got to be that tornado of a person that comes in their house. He disrupts everything, and he has good reason. Change is not easy for anybody and that’s what he’s coming in there trying to represent. You can sell that thing and we can buy it back if I make enough money growing whatever it is we grow. You can’t always get this land. It’s like we say, if you got something under your feet that belongs to you, then you got a stake in America.

The Visual Approach to the Play’s Ghost Stories Is a New Way into Wilson’s Conversation About What Haunts Black People’s Past and Present

In The Piano Lesson, ghosts are both literal and metaphorical, including the protective spirits of the Charles family attached to the piano and the racist terror that is Sutter — supposedly pushed into a well by the ghosts of Boy Willie’s father and the other men he killed in a box car fire. When trying to embody Wilson’s ghosts, Richardson Jackson went for a cinematic approach that added a more visually dramatic element to the show.

RICHARDSON JACKSON I wanted to make the metaphysical realm of ancestry as large as what I think August was experimenting with. Especially for Berniece, I kept thinking about her fear over what she encountered when she was young. As you live life and evolve, you realize how what you see when you’re young plays such an integral part in how you grow as a person. She saw her mother interact with this thing and it scared her. So that’s why she really doesn’t want to deal with it. And in a greater metaphor, I think that what August was doing was holding the power of what we don’t confront because of our fear.

There was also something August was doing, not just obvious to me, of juxtaposing Christianity with what we left behind in Africa and merging the two. It takes both of them in this context in this country to move us forward. You can’t leave the ancestry behind. That particular ghost was inherent in what that piano embodies in the sculptures, in the amount of attention that we have given that piano or that August gave that piano.

BROOKS At that exorcism at the end, Berniece realizes, “Oh, [the spirits] actually here to comfort me.” She embraces those that came before her and not just the pain of it, which is why she’s holding on to that piano. She says it’s the blood — all of the pain that her family had to endure. She’s understanding that she can also embrace the goodness of what [those spirits] have to bring, the joy. When she calls them in that song at the end, I think it is a calling of them to bring that peace into this space where there is so much chaos, so much killing and thieving. It is so broken. You see that in Wining Boy who’s dealing with alcoholism and Boy Willie who is trying to figure out what to do.

MORELAND We talked a lot about the exercising of the spirit of Sutter from this home, from this Black family. What does that look like? I wanted it to be a fight and I wanted to see the fight and I want to feel the fight. [Richardson Jackson] said she felt like it’s got to be like Capoeira — it has to be low and it’s got to be bendy. It’s got to be like The Matrix. A trailer that had just come out for one of these movies and she came in and was like, “It’s like this beam of light right here, but we probably can’t accomplish that on stage.”

RICHARDSON JACKSON I went back and forth because I didn’t want the ghost seen except as an image at the beginning for [Berniece] when she woke up. Which was really like cinema — of going backward and saying what she saw. In the end, what I wanted to occur was for the ghost to be able to see what was happening downstairs with the piano. And when I thought of the ghost of Sutter and what this white man wants, I fashioned that in my head to say, “Oh, I see what he wants. He doesn’t want the piano. He wants what the piano represents. That’s our history.”

And so it’s the ancestors that drive it out — the specter of racism. It can only be dealt with when we embrace the power from where we come from. We may not have the specificity of what particular nation of people it is, but we do know that from the continent, we had great power. We are people of that dirt, that earth, of those diamonds. We have a beginning. We were the cradle of civilization. So we can’t be afraid to confront what’s now. We have to meet that. We have to go ahead and play the piano.

JACKSON It’s the ghost of Parchman farm. It’s the ghost of [Berniece’s] husband getting killed by white people because he’s out there trying to, like Boy Willie says, keep the wolf from his door. It’s the ghost of [Boy Willie] trying to break the cycle of going back and forth to that damn prison like everybody does. It’s the history of that land or Boy Willie thinking he’s going to get it. We don’t even know that that land is going to be there. Like Wining Boy said, man might have sold the land three-four times by the time you get back there. And there’s nothing you could do about it. Black folk don’t make the law.

That’s the element [LaTanya] added. She addresses the ghosts from the beginning of the play. Sitting there when those lights go out suddenly the way they do in that theater, and hearing that “phoom” — people always go, “Oh shit, what’s going to happen?” All of a sudden, there’s a haint in the house. And her leaning into the spiritual aspect of who these people are and who their ancestors are and this malevolent ghost running around the house trying to get this heirloom back from them adds a whole other sense of ownership to an audience sitting there watching. They’ve already picked a side — even before they have a chance to pick Berniece or Boy Willie. They’ve already chosen Black people.

Through That Textual and Visual Approach of Their Director, the Play’s Stars Found a New Way Into Their Characters and the Story

All three of the show’s leads say the director’s vision offered a new angle on how they could explore the emotional turmoil of their respective characters. Those deeper turns changed performance choices, but they also offered chances for reflection, particularly for Jackson and Washington, who have played Boy Willie 30 years apart.

SAMUEL L. JACKSON There are all kinds of things that are happening there that I never thought about before when I was doing the play, but it’s great to be out there in the dynamic of everything that’s going on around me, and how I’m approaching it, and what I’m doing about it, and enjoying the energy of what this is — a reimagining of the play for me in terms of what I understand about it. I had great people around me when I did it. It’s always a wonderful thing to have actors around you that make sense of what’s going on. But I was so much louder than John David and LaTanya allows him to be. Lloyd and August had me screaming the whole play. We were tornadoes coming in that house, tearing up stuff.

WASHINGTON She knows the words and the play so well and it was so helpful to make the bold choices I had to make. She opened me up in such a way and gave me access to the feelings of what I’m interpreting — what’s possible. She kept talking about how Boy Willie is the engine, but it’s more than that. She would also talk to me about owning space and actually listening. She would talk about not necessarily concentrating on anger but frustration — and there is a difference. I think that’s her perspective. It’s easy to go into anger, especially with some of these speeches and these back and forths with words that can be read and played as anger.

BROOKS The way I walked when we were in rehearsal, [LaTanya] was saying, “Why do you walk so old?” That was so interesting to me because, personally, I’m thinking Berniece has the weight of the world on her shoulders, but that doesn’t necessarily mean she walks like she is an old lady. We were having those short hands where she understood that in ways I’m not sure white male directors might have understood. I could have convinced them that she had the weight of the world on her shoulders, so of course, she would be walking like that. But [LaTanya] has a different lens that is so true to who these people are. I feel like she’s really trying to crack into how we are supposed to be as women in this world and how that might not be what it has always been.

The Revival Is Ultimately a Deeply Personal Step onto the Stage for Its Performers

Within The Piano Lesson‘s ensemble of Black performers and creatives, several come from the South, and just as many have strong relationships to spirituality and their ancestry. Jackson notes that his own grandmother was raised by someone born into enslavement. Leaning into these personal histories helps the ensemble — which also includes Michael Potts (Wining Boy), Ray Fisher (Lymon), Trai Byers (Avery), April Matthis (Grace), Nadia Daniel and Jurnee Swan (Maretha) — better capture how Richardson Jackson brings some of Wilson’s deepest themes about legacy, agency and ambition to life on stage.

MORELAND Sam was ready to come back to the stage. LaTanya was ready to direct and so the conversation very quickly turned to John David and him wanting to put in that work. He had a conversation with his father about that work and with his mother, Pauletta, about that work and what the theater could give him. Then he had a conversation with LaTanya. Danielle [and LaTanya] met back in 2016 and so she had Danielle on her mind because she wanted a modern, regular beautiful Black woman. We talked a lot about complexion and she wanted a woman of this complexion to represent this family.

The rest of the cast was also interesting in the way in which it came together because it became a conversation of how do you create camaraderie and family and friendship in three weeks? So it was a very short list with Michael Potts. We were blessed with Trai Byers. No one knew that he was a man of God, so to end up with this man and this actor marrying the two worlds together? And [Richardson Jackson] had worked with Ray during the Arthur Miller — One Night memorial performance, and she was struck with him. She said that they only did one scene together, but she found him to be honest and that was why Lymon had to be Ray.

WASHINGTON This is probably one of the most important seasons, I’ll say, of my life. I attended a historically Black college so I feel like this is the continuation of that. This is a Graduate School of such. I’m sharing the boards with these masters — I’m particularly talking about Michael Potts and Sam Jackson. Sam, who originated Boy Willie and Michael Potts, who has done August Wilson many times over. He’s a Wilsonian. I’m getting let behind the curtain of what August Wilson is all about, what’s actually the importance of African American theater and artistry. I’m getting a first-hand look and understanding about what it means to be an African American actor.

JACKSON I loved being Boy Willie when I was being Boy Willie, but a lot of things happened during that time. Being Doaker in it now, it’s a whole other responsibility, being able to sit there and be the anchor of a family that’s in flux. With Boy Willie being what Boy Willie is and why he came home, I’m trying to change his life and the trajectory of what his life could be. Having a different perspective from wanting the piano — really doing everything possible to get the piano from Berniece and not really caring about her or her feelings.

Watching it from that perspective — and being the guy who is the linchpin there in that house, caring for [Berniece] and with having his brother come up, Wining Boy — I’m looking at it now and with different eyes in terms of watching the way [Boy Willie’s] life is playing out and what he’s doing, gambling and drinking. I’m dealing legitimately in my head now because I know what alcoholism is having been a victim and looking at him drink the way he drinks and the way he comes in and out of the house and what it all means, in terms of how long is he going to be around and I’m I gonna be the one surviving through this or will I be taking care of him eventually, too?

BROOKS It’s been challenging every night to take on these fictional spirits of Mama Ola, Papa Boy Charles and all of the aunts and uncles that Doaker talks about when he talks about them taking the piano back. But the only way for them to really live, to feel them, is if I call them my own. So every night I call on my mama, my godmother, I call on my aunts. I have to call on my close friend Darius Barnes who just passed away, who was a choreographer-dancer. And what I realized, first while filming The Color Purple movie, is that what I’m stepping into is ancestry work. And when I hear audiences in awe, that to me is like, you understand what that is. You understand what that means. So I have to honor that because I feel as storytellers we are being representative of people. It’s my duty to be that voice for someone else on stage.

MORELAND It’s in the Jacksons’ blood to advocate, educate and fight for Black people, specifically. It is in the fabric and the DNA of the Washingtons’ to advocate, educate and fight for Black people. Ray Fisher — as a point of his own — has it. Danielle Brooks has it. Trai Byers has it. Michael Potts has it. And they all talk about it.

If you liked the article, do not forget to share it with your friends. Follow us on Google News too, click on the star and choose us from your favorites.

For forums sites go to Forum.BuradaBiliyorum.Com

If you want to read more Like this articles, you can visit our Social Media category.