#The Price of Desire Movie Review

Table of Contents

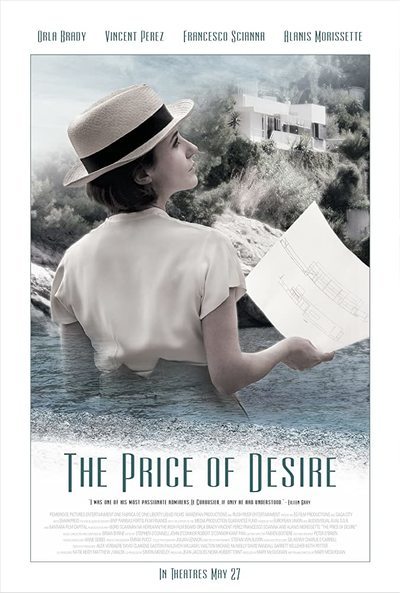

“The Price of Desire”

Halina Dyrschka, the director of this year’s essential documentary, “Beyond the Visible—Hilma af Klint,” recently told me how tired she had grown of “victim narratives,” the overabundance of which shift focus away from the visionary achievements of their female subjects. No matter how much effort was put into replicating the spareness and pragmatic elegance of Gray’s designs, her work is repeatedly rendered out of focus. Only toward the end, when an elderly Gray feels the contours of her Bibendum chair to ensure it has been given the proposer number of centimeters do we get an understanding of the palpable sensuality she infused into every piece of furniture. When she gives a tour of her celebrated villa, the camera inexplicably focuses not on the surrounding space but on Gray’s radiant face, beaming with pride at the details that have been obscured from our view. As fellow architect Mies van der Rohe famously observed, “God is in the details,” while affirming that “less is more.” If only the filmmakers had heeded the latter quote.

The frenzied editing that appropriately accompanies the film’s title sequence, which stages the auction where a piece of Gray’s furniture was sold for a record-breaking price, regrettably extends throughout the majority of the film, never allowing the visuals or even the dialogue to resonate as they should. For a film supposedly espousing the merits of minimalism, it sure comes off as a cluttered mess, complete with fade outs that are so abrupt, it’s as if they’re cutting to a commercial break. Brian Byrne’s irritatingly persistent score exemplifies how the filmmakers are too timid to fully embrace the stillness that would’ve enabled Gray’s artistry to dominate the frame as well as the narrative. Instead, we are subjected to an insufferable number of whiny monologues delivered directly to the lens by Le Corbusier (Vincent Perez), the iconic architect idolized by Gray. So incensed was he by her refusal to conform to his arrogant principles that he weaseled his way into her villa and covered its walls with vulgar wall murals, just as a dog would mark its territory. What’s equally infuriating is how his running commentary through various sequences emerges as its own unwelcome intrusion, hijacking what should’ve been Gray’s film every time he mansplains to us.

No less loathsome is Gray’s lover, architectural journalist Jean Badovici (Francesco Scianna), who encourages her to create e1027—which she designed as a monument to their love—only to betray her by taking credit for it, claiming himself to be the building’s joint architect. The film fails to convey what possessed Gray to continuously fall back into his arms, even after she found him in bed with her own younger doppelgänger. It’s a shame more time wasn’t spent on other areas of Gray’s life, such as her relationships with women including the singer Damia (Alanis Morissette). Though the prodigiously gifted Morissette earns fourth billing, her role amounts to little more than a glorified cameo (she had more to do as the nose-booping God in “Dogma”). Another famous name that makes its way into the credits is that of Julian Lennon, whose sole role in the production was that of unit photographer, and the stills he lensed are certainly more interesting than anything in the final cut. As for Orla Brady as Gray, her performance is strong but underutilized. Too many scenes require her to simply stand around looking beautiful, or in one case, dance in slow motion to a meaningful tune only she can hear. Once death reared its inevitable head in the final reel, I felt a glimmer of relief as the picture ground to a halt, prompting me to savor some of cinematographer Stefan von Björn’s compositions, such as the moment where Gray stares down at Le Corbusier from her perch on a staircase, dwarfing his stature as he sheepishly stumbles, half-naked, out of frame.

There’s no question that this movie was a labor of love, which makes its shortcomings all the more heartbreaking. Why couldn’t Gray serve as our fourth-wall breaking narrator rather than Le Corbusier, who sullies every moment he’s onscreen with his tiresome mustache-twirling and artless exposition? The only satisfying moment in the picture occurs when soldiers use his self-righteous vandalism for target practice. McGuckian and her team should be commended for bringing Gray and the injustices that befell her back into the international discourse, yet their film does not do the great architect justice. When asked about whether she’s upset about being robbed of her intellectual property rights, not to mention the ownership of her own villa, Gray explains, “I prefer to do things rather than possess them.” Perhaps Hilma af Klint, the pioneering abstract artist, would’ve been a kindred spirit to Gray, since she found fulfillment in the creation of her work rather than the rewards it could reap. Yet I suspect neither woman would’ve appreciated having their own biopics be dominated by the men who sought to silence them in life. Imagine a film about af Klint where she’s constantly interrupted by Rudolf Steiner, and you’ll have a fair approximation of the missed opportunity that is “The Price of Desire.”

Available on VOD today, 6/2.

Matt Fagerholm

Matt Fagerholm is an Assistant Editor at RogerEbert.com and is a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association.

The Price of Desire (2020)

Rated NR

108 minutes

about 6 hours ago

about 6 hours ago

1 day ago

1 day ago

If you want to read more Like this articles, you can visit our Social Media category.

if you want to watch Movies or Tv Shows go to Dizi.BuradaBiliyorum.Com for forums sites go to Forum.BuradaBiliyorum.Com