#Satellites have become smaller — so even you can do science in space

Table of Contents

“Satellites have become smaller — so even you can do science in space”

This month, the SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft will make the first fully-private, crewed flight to the International Space Station. The going price for a seat is US$55 million. The ticket comes with an eight-day stay on the space station, including room and board – and unrivaled views.

Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin offer cheaper alternatives, which will fly you to the edge of space for a mere US$250,000-500,000. But the flights only last between ten and 15 minutes, barely enough time to enjoy an in-flight snack.

But if you’re happy to keep your feet on the ground, things start to look more affordable. Over the past 20 years, advances in tiny satellite technology have brought Earth orbit within reach for small countries, private companies, university researchers, and even do-it-yourself hobbyists.

Science in space

We are scientists who study our planet and the universe beyond. Our research stretches to space in search of answers to fundamental questions about how our ocean is changing in a warming world, or to study the supermassive black holes beating in the hearts of distant galaxies.

The cost of all that research can be, well, astronomical. The James Webb Space Telescope, which launched in December 2021 and will search for the earliest stars and galaxies in the universe, had a final price tag of US$10 billion after many delays and cost overruns.

The price tag for the International Space Station, which has hosted almost 3,000 scientific experiments over 20 years, ran to US$150 billion, with another US$4 billion each year to keep the lights on.

Even weather satellites, which form the backbone of our space-based observing infrastructure and provide essential measurements for weather forecasting and natural disaster monitoring, cost up to US$400 million each to build and launch.

Budgets like these are only available to governments and national space agencies – or a very select club of space-loving billionaires.

Space for everyone

More affordable options are now democratizing access to space. So-called nanosatellites, with a payload of less than 10kg including fuel, can be launched individually or in “swarms”.

Since 1998, more than 3,400 nanosatellite missions have been launched and are beaming back data used for disaster response, maritime traffic, crop monitoring, educational applications and more.

A key innovation in the small satellite revolution is the standardization of their shape and size, so they can be launched in large numbers on a single rocket.

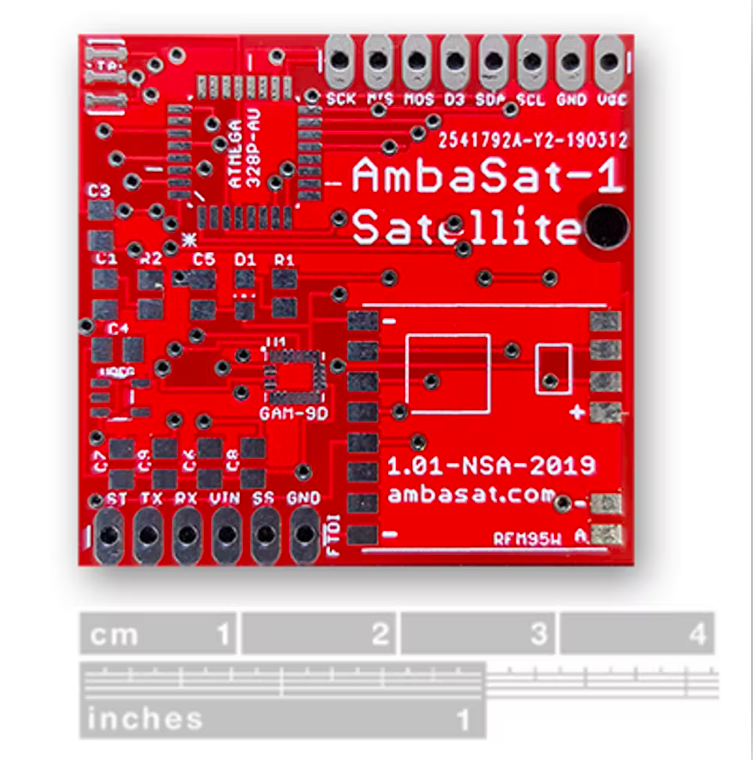

CubeSats are a widely used format, 10cm along each side, which can be built with commercial off-the-shelf electronic components. They were developed in 1999 by two professors in California, Jordi Puig-Suari and Bob Twiggs, who wanted graduate students to get experience designing, building, and operating their own spacecraft.

Twiggs says the shape and size were inspired by Beanie Babies, a kind of collectible stuffed toy that came in a 10cm cubic display case.

Commercial launch providers like SpaceX in California and Rocket Lab in New Zealand offer “rideshare” missions to split the cost of launch across dozens of small satellites. You can now build, test, launch and receive data from your own CubeSat for less than US$200,000.

The universe in the palm of your hand

Small satellites have opened exciting new ways to explore our planet and beyond.

One project we are involved in uses CubeSats and machine learning techniques to monitor Antarctic sea ice from space. Sea ice is a crucial component of the climate system and improved measurements will help us better understand the impact of climate change in Antarctica.

Sponsored by the UK-Australia Space Bridge program, the project is a collaboration between universities and Antarctic research institutes in both countries and a UK-based satellite company called Spire Global. Naturally, we called the project IceCube.

Small satellites are starting to explore beyond our planet, too. In 2018, two nanosatellites accompanied the NASA Insight mission to Mars to provide real-time communication with the lander during its decent. In May 2022, Rocket Lab will launch the first CubeSat to the Moon as a precursor to NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon by 2024.

Tiny spacecraft have even been proposed for a voyage to another star. The Breakthough Starshot project wants to launch a fleet of 1,000 spacecraft each centimetre in size to the Alpha Centauri star system, 4.37 light-years away. Propelled by ground-based lasers, the spacecraft would “sail” across interstellar space for 20 or 30 years and beam back images of the Earth-like exoplanet Proxima Centauri b.

Small but mighty

With advances in miniaturization, satellites are getting ever smaller.

“Picosatellites”, the size of a can of soft drink, and “femtosatellites”, no bigger than a computer chip, are putting space within reach of keen amateurs. Some can be assembled and launched for as little as a few hundred dollars.

A Finnish company is experimenting with a more sustainably built CubeSat made of wood. And new, smart satellites, carrying computer chips capable of artificial intelligence, can decide what information to beam back to Earth instead of sending everything, which dramatically reduces the cost of phoning home.

Getting to space doesn’t have to cost the Earth after all.

This article by Shane Keating, Senior Lecturer in Mathematics and Oceanography, UNSW Sydney and Clare Kenyon, Astrophysicist and Science Communicator, The University of Melbourneis republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shane Keating and Clare Kenyon will be discussing CubeSats and the Space Bridge program at Design beyond Earth: The future of Earth observation, an in-person and online event at Scienceworks in Melbourne on Sunday March 27, 12pm-1pm.![]()

If you liked the article, do not forget to share it with your friends. Follow us on Google News too, click on the star and choose us from your favorites.

For forums sites go to Forum.BuradaBiliyorum.Com

If you want to read more like this article, you can visit our Technology category.