Watch ‘Ballad of a White Cow’ Review: An Iranian Widow Seeks Justice

Table of Contents

“Watch Online ‘Ballad of a White Cow’ Review: An Iranian Widow Seeks Justice”

“‘Ballad of a White Cow’ Review: An Iranian Widow Seeks Justice”

If all of this sounds like a recipe for a thoroughly depressing spiral toward the bottom, à la “Bicycle Thieves” and its neorealist ilk, think again. Sure, “Ballad” can be brutal, but Moghaddam and co-helmer Behtash Sanaeeha (who first collaborated on “Risk of Acid Rain”) also see it as a story of resilience in a society that puts enormous limits on women. In some ways, “Ballad” feels engineered to put a maximum number of obstacles in Mina’s path, but as executed, the movie doesn’t feel the slightest bit didactic, despite its unusually stiff style.

Nearly every shot in this film is film is locked down and squared off, staring either straight at or directly perpendicular to its characters, like a Wes Anderson movie, minus all the wallpaper and whimsy. You could count on one hand the number of times DP Amin Jafari’s camera moves, and yet, this restraint reads as solemn noninterference. The co-directors seem determined to avoid the semblance of sentimentality or emotional manipulation. The duo are clearly fans of populist cinema, judging by the importance movies play to their characters (Bita is named for a popular 1972 local hit, and loves cinema infinitely more than school), but they’ve taken a more formalist approach to their own work: precise compositions, few if any closeups, no music.

But amid such austerity (which can be taxing at times), the humanism shines through, centered in Moghaddam’s dignified performance, one that shifts depending on whether the character is being observed in public or private. It’s as if the film is saying that being a woman in Iran demands a certain level of performance: She’s allowed to grieve — and it’s a wrenching scene, even captured at a distance — when she learns of the mistake that would have exonerated her husband, had the truth come to light before his execution.

In most other situations, Maryam is obliged to dial down her emotions, to make herself practically invisible (as she does at her factory job, all but disappearing among the milk cartons) and to mask her beauty. In the rare scenes when she applies lipstick or removes her headscarf, the gesture conveys determination, even if it’s being done for a man’s benefit. She cries twice in the film, and in both cases, it’s a balancing act of composure and weakness. We meet the character en route to the prison where her husband Babak is soon to be hanged, and the movie is modest enough to pull back from their farewell visit, allowing the cell door to swing shut on this private moment.

Later, we’ll learn that both Maryam and Babak believed he was guilty, which explains why they didn’t challenge the sentence. Turns out, it was the witnesses who were unreliable, but guiltier than that is the system that might allow such a miscarriage. That burden falls especially heavily on the shoulders of the movie’s other main character, Reza (Alireza Sanifar), who served as one of the judges in Babak’s trial. “Ballad” doesn’t reveal this connection right away, but it’s an essential detail to mention here, since the movie is quite sly in the way it handles which characters know certain things and when.

Shortly after Mina receives the news of her husband’s innocence — along with the promise that she will be compensated “the full price of an adult male” — Reza pays her a visit. Rather than begging her forgiveness for passing a faulty sentence, he poses as an old friend of Babak’s, writing a generous check for a nonexistent debt. In the weeks to come, these two characters will grow closer, and had this been a Hollywood romance, Reza’s lie of omission would serve as the secret that threatens their relationship (which it does, in a less contrived way).

But Reza isn’t the only one who chooses to hold information back: Mina’s landlady objects to the fact she let “an unrelated man” into her house — meaning Reza — forcing the widow and her daughter to vacate the apartment. But Mina never tells Reza he’s responsible for this latest setback. The judge thinks he’s doing Mina a favor by offering her to lease his own apartment at a vastly discounted price, when in fact, he’s the cause of her eviction. In Reza’s case, his dishonesty is a sign of weakness, whereas with Mina, her discretion represents a kind of strength — one that grows increasingly impressive as the film unfolds.

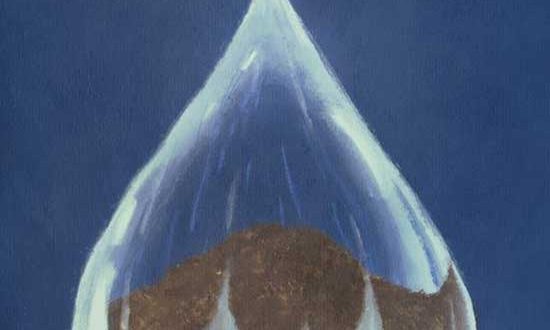

Moghaddam and Sanaeeha (who co-wrote the script with Mehrdad Kouroshnia) find multiple opportunities to show non-Iranian audiences how local customs limit a woman’s options. Religion is clearly responsible for much of what they find objectionable — as when Reza’s peers insists that his mistake must have been “God’s will” — and yet, they never come out and criticize it outright. The Quran actually provides the metaphor of the film’s title, as well as its opening vision: The Surah of the Cow refers to a sacrifice Moses demanded for a man’s death, represented here by an innocent, computer-generated white cow ready for slaughter.

This image appears twice in “Ballad,” a rare glimpse into Maryam’s head, but an important clue as to the fantasy — which involves a symbolic glass of warm milk — that closes the film. From a Western perspective, audiences want to see things work out for Maryam, but by the logic of Iranian custom itself, the film asks a tougher question: In an eye-for-an-eye society, what kind of compensation is fair for her loss? Blood money doesn’t cut it, especially when Barak’s father and brother want a share. But what about blood?

If you liked the article, do not forget to share it with your friends. Follow us on Google News too, click on the star and choose us from your favorites.

For forums sites go to Forum.BuradaBiliyorum.Com

If you want to read more Like this articles, you can visit our Watch Movies & TV Series category